Privateers, Puritans, and Merchant Capitalists: The rise of England and Holland.

Introduction. One legacy of early modern Europe was the expansion of wealth and the search for new markets. Crusaders took the Holy Land back only to be left with it to defend. They didn’t hold onto it for very long. As this ideal foundered, returning Crusaders returned to Europe with a renewed demand for goods that was previously forgotten in Europe. New luxury goods, such as spice and frankincense, entered the European markets from the east. Additionally, the black plague, which killed up to one third of Europe’s population, had a silver lining. It left a considerable amount of wealth behind. Survivors of this terrible disease inherited estates, and these inheritances included peasants as well as privileged. As the continental wars in Europe tightened the political boundaries across the continent, other nascent nation-states looked to the seas to expand their markets. In this effort to organize an expansion overseas they used different methods than did the Spanish and Portuguese. The latter’s expansion into the New World was organized from the top down, hence the governments of Spain and Portugal played a heavy hand in influencing their New World colonies and trade networks often with a spoils system. Contrasting this were the models of England and Holland. Their initial ventures into this new frontier were from the bottom up because the state coffers did not allow these small but growing states to pour money into the unknown. Unlike Ferdinand and Isabella, Charles V, and Phillip II, Elizabeth I could not afford to take such risks, politically and financially, by supporting through direct patronage a mission to colonize overseas territory. Instead the English, and soon after the Dutch, found creative ways to finance their quests for a market share of the New World.

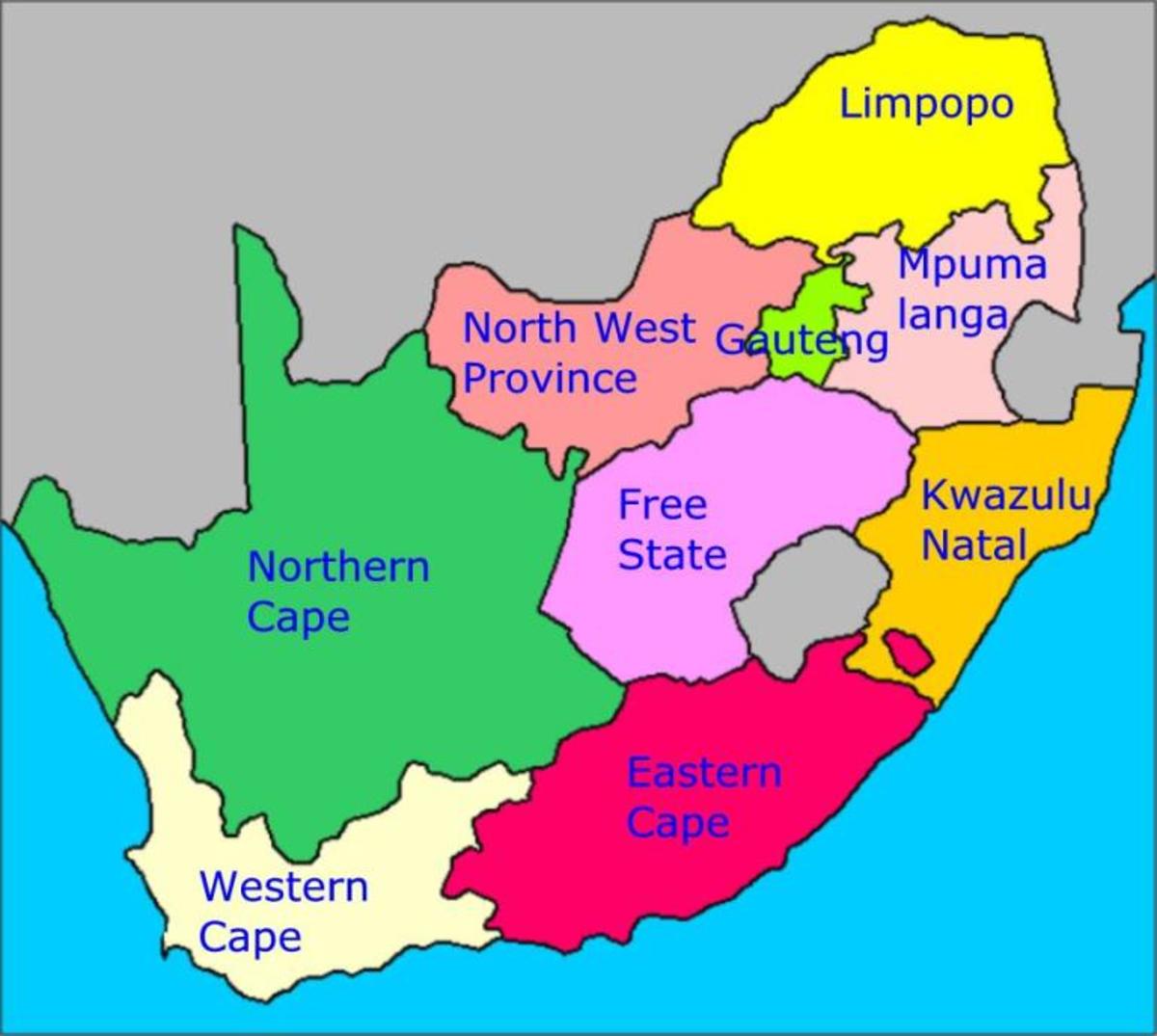

If you look at Holland on a European map in the 16th century its territory is nothing extraordinary, but its location was vital. The roots of Holland’s ascendancy as a financial power date to the Middle Ages when Flanders became a center of commerce. Much of this focus centered on the wool industry. Their ships, relative to the Portuguese, were lighter, faster, and cheaper, and coupled with their cheap textiles, metal goods, and extensive credit, the Dutch soon monopolized European cargo trade. Baltic grain was another commodity that they cornered and Amsterdam quickly became a commercial and banking center of the United Provinces in the sixteenth century. The Dutch and English refined the joint stock company, a process where the investors shared the profits from the investments made or bought. These were in effect government-enforced monopolies. Governments could levy taxes and duties on the trade in an effort to gain a favorable balance of trade (Koenisgberger, 103). The United Provinces of Netherlands, as they came to be called, were primarily governed by bankers and merchants (Kb, 104). Although the Dutch were subjects of Charles V’s far-flung empire based in Spain and Austria, the Dutch had an independent streak which was a factor that propelled them towards Protestantism during the Reformation. The Dutch infrastructure of trade and commerce was already well-established before they ventured overseas. The Dutch had merchants in the Hanseatic ports and competed fiercely with Luebeck and Venice for market share during the late Middle Ages. During this time the Dutch dealt heavily in buying foods and products from landed nobles in northern Europe which they would then ship to Amsterdam for further distribution (Kb, 40). Acting as middlemen the Dutch were indirectly responsible for prolonging serfdom east of the Elbe, as northern European states such as Prussia bought into their integrated markets and networks rather than develop their own hinterlands. Like England, the Dutch enjoyed a state-sponsored king, which helped stifle competition against increasingly weaker trading republics that operated as city states, namely Venice and Luebeck. Two factors helped further the Dutch – the overseas discoveries and the opening of the overseas routes around Africa. At this point the center of European commercial life shifted permanently to the Atlantic seaboard from the Mediterranean (Kb, 101). The technology of the northern European countries also started to eclipse that of Mediterranean counterparts. By the turn of the sixteenth century, Dutch and English flutes were faster and better armed than the Portuguese carracks. They were also cheaper, transporting goods that didn’t cost them as much because of their proximity to textile markets for instance (Kb, 102). It’s no wonder the Russian Tsar, Peter, went to Holland to learn how to build ships.

Merchant Capitalists. England was slow to venture overseas which is surprising considering its location relative to the New World. After all it was Saint Brendan who probably reached Greenland from Ireland, and the Vikings who had invaded the British Isles, used it as a steeping stone to reach Greenland and the Labrador. England was embroiled in its own internal problems, namely the strife caused by Henry VIII’s male succession and subsequent break with Rome, which distracted it from abroad until the reign of Elizabeth I. Even then England remained cautious and less aggressive than Spain’s approach to colonization. The first overtures England made into the Atlantic were exploratory ventures seeking the fabled Northwest Passage to Cathay (China). Martin Frobisher made three expeditions between 1575 and 1578. Still, it wasn’t the direct patronage of Elizabeth I, but from the Muscovy Company, a chartered joint stock company, which sponsored his voyage after some reluctance. The Muscovy Company, up until then, had a monopoly on trade between England and Russia. It was consortiums such as these which were typically taxed by the monarchs, hence filling the state coffers with revenue. And it was navigators such as Henry Hudson, a Dutchman who sailed for England between 1607 and 1611, better known for his discoveries, that led the English efforts into the high seas. Francis Drake was another great English navigator. The first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe, he was second in command of the English navy when they defeated the Spanish Armada, but he is better known for his efforts as a privateer.

Puritans, Separatists, and Pilgrims. There were different types of English Protestants who played a significant part in English colonization. The Puritans of England were a group of Anglicans who sought to purify the Church of England of its Catholic rituals and practices. After Henry VIII split from Rome there was little difference between the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church. Other than a transfer of governance and the abolishment of the monasticism in England, institutionally there was little difference between the two. Pre-Reformation criticism of Rome was not novel in England and there were groups who insisted that the Church of England go further in their reforms and that it was too tolerant of Catholic practices. These dissenters were in the minority and the issue of further reforms was sensitive as many English had not fully accepted Henry’s split to begin with. Abolishing the episcopacy and replacing it with congregational governance and modifying the Book of Common Prayer were platforms of the Puritans. While the Puritans eventually grew in political and social influence in England they are arguably best known for the theocracy that they established in Massachusetts. The Plymouth Colony (1620-1691) and was closely related with the joint-stock companies. Making a profit was an equally strong incentive for maintaining these tenuous overseas colonies. James I formed two joint stock companies in 1606 – the London Company and the Plymouth Company. Jamestown, Virginia was established by the former and each was given a territory to govern. Collectively the two were known as the Virginia Company. At Plymouth however, many of the original settlers were fleeing religious persecution but they still needed financing to make the move and that’s where the joint stock companies played a hand. The origins of the Plymouth settlers, or Pilgrims, began in Scrooby, Nottinghamshire, England. Led by John Robinson, William Brewster, and John Bradford, the congregation of Puritans, or separatists, came under pressure from the decisions of the Hampton Court Conference and the crackdowns that followed. In 1609 the Scrooby congregation immigrated to the Netherlands which had a more tolerable religious climate. Settling in industrial and commercial Leiden was much different than pastoral Scrooby and the Pilgrims felt further pressure from culture shock of a foreign language and land. The English Crown’s long arm also found its way to Netherlands and attempted to arrest Brewster for inflammatory literature critical of England. The Pilgrims then applied for a land grant from the London Virginia Company in 1619 in an effort to distance themselves from England. Financing their debt were merchant adventurers who saw colonies as a means to an end – to make a profit. Finally the group left Netherlands in 1620 aboard the Speedwell and headed towards Southampton to join the sister ship, the Mayflower. Although the Puritans would eventually settle outside of their company’s grant, their charter was reorganized and governed by the Mayflower Compact, a document which drew up rules by ship members to live and survive in an unknown and hostile new world in the presence of God …. William Bradford was elected the colony’s first governor (Carnes and Garraty, 35).

East India Company. The East India Company was started as a joint stock enterprise when it was charted by the crown on December 31, 1600. It was formed by London merchants, or Merchant Adventurers, who were similarly involved with the Muscovy Company and the Levant Company. Their application to Elizabeth I in 1599 was based on the premise that conducting trade in the distant and remote east could only be done by forming a joint stock enterprise (Smith, 303). It wasn’t long after that the English clashed with the Dutch in the East Indies. A Dutch massacre of ten Englishmen in 1623 at Amboina inflamed English sentiment against their new rival. At this point the East India Company increased its presence on the sub-continent’s trading stations: Madras, Surat, and Calcutta. Within thirty years England would find itself at war with the Dutch mostly because of trade. The Navigation Act of 1651 was an effort to reign in some of England’s commercial trade wealth by limiting commercial imports to English ships. It was aimed primary at curtailing direct Dutch shipping to the colonies and from India and to give England and the colonies a bigger share of the carrying trade. Strong lobbyists of the East India Company were behind the efforts to push this act through Parliament (Smith, 343). War with the Dutch was almost inevitable as the two filled in the void of a declining Spain and Portugal. The Dutch were more dependent upon commerce and foreign trade than the English and the two navies and merchant fleets were equally matched. Between 1652 and 1654 the two countries fought various naval battles but the English naval blockade eventually forced the Dutch hand and they sought peace rather than face starvation (Smith, 344). Despite the victory the costs for the English proved Pyrrhic as new taxes were issued to pay for the war’s expenses. The Dutch came away from the war with virtually no damage to their vast merchant fleet.

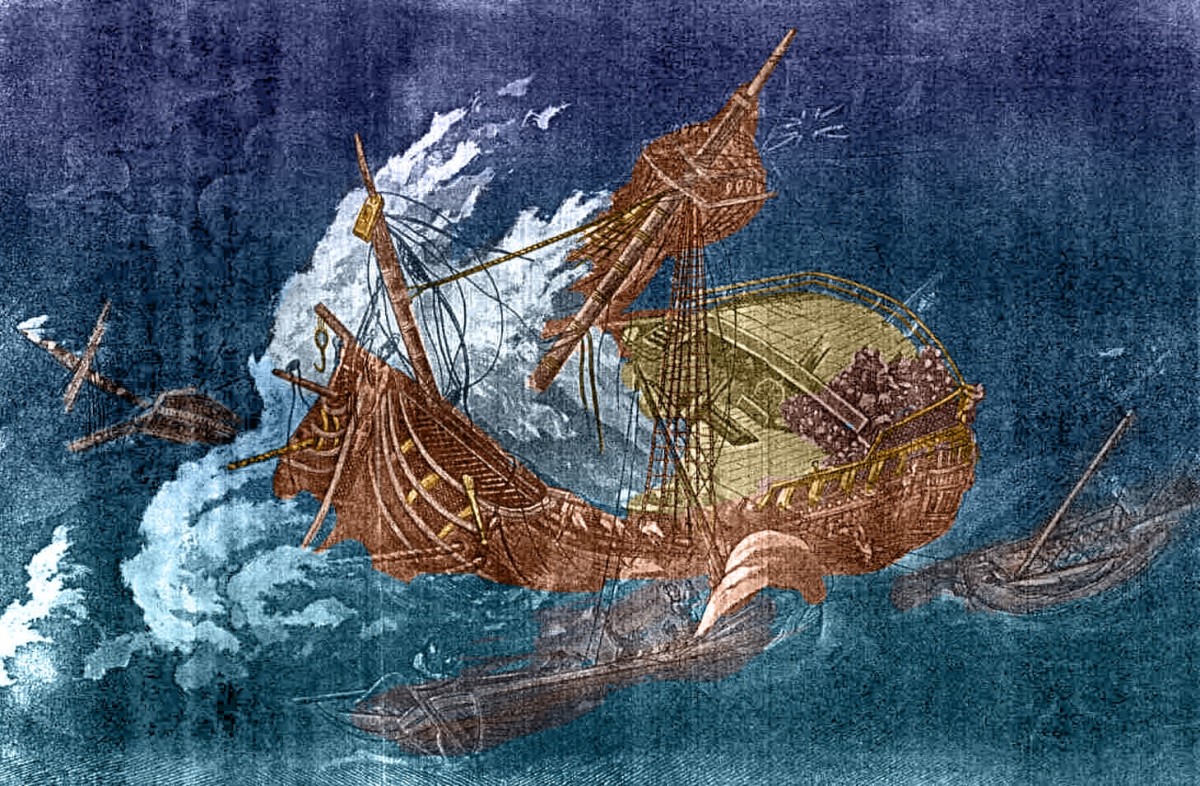

Dutch East India Company. Holland’s answer to the constant fighting, wars, and decadence of continental European monarchs was to open a company, the first to issue stock, and finance overseas trade on a large scale. Originally established as a monopoly with a 21 year grant by the States-General of Netherlands the Dutch East India Company was responsible for Dutch trade overseas. On behalf of the Dutch government it was given the right to wage war, negotiate treaties, establish colonies, and coin money. It was in effect, the private arm of the Dutch government that operated overseas and was financed by common stock holders. It was also hugely successful and its annual return (dividend) over a 200 year stretch ending in 1798 was said to be 18%. By the late 16th century the Dutch targeted Portuguese trade routes and colonies. The Portuguese has dominated the spice trade up to this point and had found a way to cut Dutch merchants out of the distribution by using Hamburg as a port. Sensing a threat from the Portuguese, the Dutch moved quickly to contain, exploit, and ultimately break Portugal’s share of the spice trade. The Portuguese trade was seen as inefficient and they were unable to supply the growing demand for spices such as Pepper, which caused a spike in the prices. It’s no surprise that former Portuguese colonies were superimposed by the Dutch: Galle (Sri Lanka), Nagasaki, Malacca, and possessions in Indonesia, for example. All of these events did not happen overnight beginning with the formation of the Dutch East India Company. Before its inception trading companies typically lasted as long as the voyage. Once shipment was received the company was liquidated because the markets were too volatile and could collapse at any time. A number of reasons contributed to the volatility and risk of these voyages: disease, shipwreck, and piracy were constant threats. Starting in 1598 competition amongst the Dutch increased as fleets set out to bring home spices and profits as high as 400% were made when Jacob Van Neck’s expedition of 1599-1600 returned from the East Indies. The Dutch then formed alliances with local Indonesian tribes against the Portuguese in return for exclusive trading privileges with the Hitu, near Ambon. In order to manage the risk of market collapse the Dutch formed a cartel in order to better control supply. The Dutch also did this to hedge against their growing rivals, the English, which formed the monopolistic East India Company in 1600.

Privateers. Often mistaken as pirates, privateers were private warships that were decreed with a letter of marque by their respective countries to attack merchant vessels during wartime. The design was to capture merchant vessels for booty and to seize the ship for the mother country. Best known among privateers was probably Sir Francis Drake who harassed and plundered the Spanish fleet for its famous gold-bearing galleons. He also attacked Spanish settlements in the New World. Captain Christopher Newport was perhaps more successful that Drake and led various attacks on the Spanish. He also captured a Portuguese ship in 1592 worth half a million pounds. Christopher Newport also commanded the three ships that sailed to found the Jamestown settlement in 1607. John Smith, reputedly a trouble-maker, was aboard this voyage, and would later go on to firmly establish Jamestown despite the hardships of its early years. The well known Sir Henry Morgan, for which the famous rum was named, conducted missions from his base in Jamaica and attacked Spanish interests across the Caribbean. England and Netherlands both used privateers against one another in their respective wars. In the first war, between 1652 and 1654, the English privateers captured 1000 Dutch merchant ships. The Dutch used privateers no less, especially in the second (1665-67) and third (1672-74) wars between the two where they were victorious because of the heroics of Admiral de Ruyter and his raid up the Thames. Interestingly, New Amsterdam (New York) was captured by the English in 1664 which contributed to the second Anglo-Dutch War.

References:

Carnes, M.C., & Garrity, J.A. (2008). The American Nation: A History of the United States, 13th ed. New York: Pearson.

Koenigsberger, H.G. (1987). Early modern Europe 1500-1789. London: Longman.

Smith, G. (1957). A history of England, 2nd ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.